“…to those who ask why the word [persons] should include females the obvious answer is why should it not?” – Lord Chancellor, Privy Council

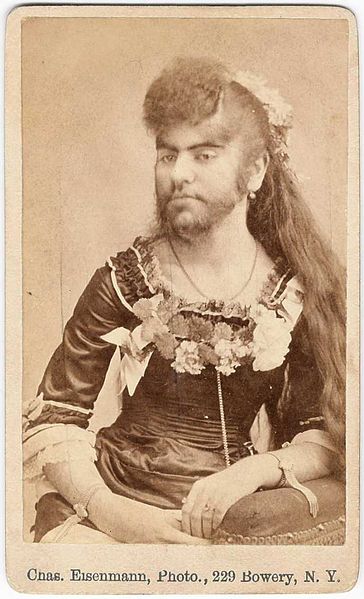

In every generation, there is always a rabble-rouser, someone who inserts themselves directly into a well-established precedent or issue, shakes it up, turns it sideways and then challenges its credibility just when it becomes most vulnerable. In 1916, rabble-rouser Emily Murphy and four friends tried to attend the trial of Alberta, Canada women accused of prostitution. The friends were ejected by the court citing the testimony was unfit for “mixed company.” Murphy appealed the to the Attorney General of Alberta stating, “If the evidence is not fit to be heard in mixed company, then … the government..[must] set up a special court presided over by women, to try other women.” The attorney general not only agreed, he appointed her a court magistrate judge.

By 1918, women throughout Canada, with the exception of Quebec, had been given the right to vote, but the British North America Act (BNA Act) which defines the operation of Canada’s government, refers to those eligible in the plural as “persons” and in the singular (he), thus it was believed for years that women could not hold office.

The British North America Act was cited on Murphy’s first day on the job as judge, when a defense lawyer challenged her position because women were not “persons’ under the law. In fact, when Murphy again challenged the notion that women were not “persons” and could therefore not hold an office, she was able to get more than 500,000 people to sign a petition asking Canada’s Prime Minister to appoint her a senator. Although he said that he would love to (not very sincere) ,his hands were tied addressing the 1876 British common law ruling stating “women were eligible for pains and penalties, but not rights and privileges.”

Rabble-rouser Murphy could not be stopped. She found five GIRLFRIENDS to sign a petition (Canada needs five

people to sign a petition when asking for constitutional clarification), and the Famous or Valiant Five became legendary.

On October 19, 1927, the Governor General asked the Supreme Court for clarification: “Does the word ‘Persons’ in section 24 of the British North America Act, 1867, include female persons?”

The Supreme Court heard the case on March 14, 1928, issuing a decision on April 24, 1928. SPOILER ALERT: Women WERE NOT qualified Persons! The court interpreted the BNA Act narrowing suggesting that when it was written, women could not hold office so OBVIOUSLY, they didn’t mean women.

SHOCK, ANGER, BETRAYAL, FRUSTRATION: The Famous Five – Emily Murphy, Nellie McClung, Irene Parlby, Louise McKinney and Henrietta Muir Edwards – were relentless, appealing to the Privy Council in England (Canada’s highest court during that time).

Six months later, on October 18, 1929, the Lord Chancellor of the Privy Council, Lord Sankey, announced their decision – “that the exclusion of women from all public offices is a relic of days more barbarous than ours. And to those who would ask why the word “person” should include females, the obvious answer is, why should it not?”

The ruling did not give Murphy her senate appointment, instead, Cairine Reay Mackay Wilson, daughter of liberal senator Robert Mackay would earn that honor. Eighty years later, in October 2009, the Valiant/Famous five were given the title of “honorary senators,” which really meant nothing because they were dead and couldn’t rabble-rouse anymore. How convenient.